Tuthmosis I (1524-1518)

Apparently Amenhotep I had no surviving offspring, at least none that can be identified with any certainty, and so the throne passed to a commoner by the name of Tuthmosis. All we know about his family is that his father was an unnamed army officer and his mother was a woman named Seniseneb (shown, right, with her son). He was a soldier himself and had obviously distinguished himself in earlier campaigns before he was chosen as the next pharaoh. He was given a princess of the royal blood to be his wife—descent through the female line was very important during this period—and was apparently made co-regent sometime before Amenhotep died.

his family is that his father was an unnamed army officer and his mother was a woman named Seniseneb (shown, right, with her son). He was a soldier himself and had obviously distinguished himself in earlier campaigns before he was chosen as the next pharaoh. He was given a princess of the royal blood to be his wife—descent through the female line was very important during this period—and was apparently made co-regent sometime before Amenhotep died.

He had full-grown children and was probably middle aged when he succeeded to the throne. He reigned for only six years (unless you include a co-regency of uncertain length), but certainly made the most of his time. He fought three major campaigns in his first three years as first Nubia and then princes of Canaan (Retjenu) rebelled. According to Ahmose of Ebana, who served with him, he inflicted devastating defeats on all of his enemies and erected victory stele at the Fourth Cataract in Nubia and across the Euphrates, somewhere near Carchemesh. As a soldier, he was very popular with the army and increased its size considerably during his rule. With its backing he was able to ensure that his men were placed in key positions within the civil and religious hierarchy of the state. His wars proved to be highly profitable and an unprecedented wealth of tribute was at his disposal.

Although the new pharaoh left his mark at many Egyptian temples, it was Karnak that received most of his attention. As an royal outsider he could not stress his family connection to the throne and chose to link himself more closely to his Amun. On a cosmic level at least, all Egyptian pharaohs since the Middle Kingdom were held to have been fathered by the god, but the concept was given particular emphasis by the Tuthmosid family and the ‘divine birth’ figured prominently in the art of the period.

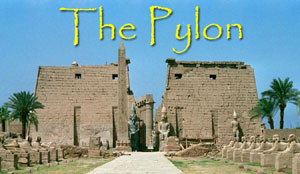

Pylon V from the West. The girl is sitting on the feet of a broken Osiride statue

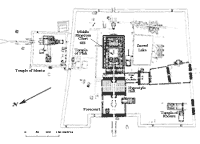

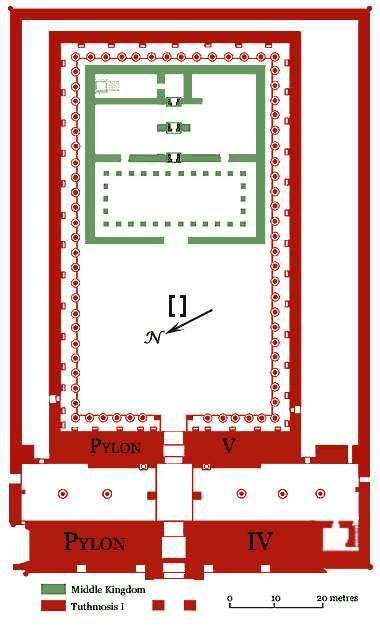

It seems likely that his work at Karnak was a continuation of that of his predecessor and he employed the same architect, Ineni, to carry it out. That is not to say that he did not modify or expand upon the original design. He began by enclosing the Middle Kingdom Temple and the forecourt added by Amenhotep I with a sandstone wall entered by a massive new gateway, Pylon V. Some time later, a new enclosure wall surrounding the earlier one was built, with an even bigger pylon, Pylon IV, to serve as the principal entrance to the temple. However, there is every reason to believe that this second phase of construction was completed (if not begun) by Tuthmosis III, his grandson.

GoogleEarth view of Karnak showing Pylons IV & V

Pylon V is in a very ruined condition but enough remains to show that it was constructed of sandstone blocks faced with limestone. It was very much smaller than Pylon IV , being only about half as broad and not nearly so tall (one assumes). There were niches and pink granite bases for a pair of flagstaffs flanking the gateway. The area within the new enclosure, including the existing forecourt, was thoroughly remodelled and was now known as the ‘august colonnade that makes the Two Lands festive with its beauty.’ It was essentially one large peristyle court with colonnades of sixteen-sided columns on all four sides. These framed niches in which stood statues of the king in the form of Osiris, lord of the Afterlife. Presumably the barque shrine that had recently been built by Amenhotep was still standing—although, given the thorough working over that the area received at the hand of Hatshepsut and then Tuthmosis III, we cannot be certain.

the new enclosure, including the existing forecourt, was thoroughly remodelled and was now known as the ‘august colonnade that makes the Two Lands festive with its beauty.’ It was essentially one large peristyle court with colonnades of sixteen-sided columns on all four sides. These framed niches in which stood statues of the king in the form of Osiris, lord of the Afterlife. Presumably the barque shrine that had recently been built by Amenhotep was still standing—although, given the thorough working over that the area received at the hand of Hatshepsut and then Tuthmosis III, we cannot be certain.

The outer pylon, Pylon IV (right) was known as ‘Amun-Re, Mighty of Prestige’ and sat about 16 metres west of Pylon V and on the same alignment. It is in a ruinous condition today but originally measured 66 by 10.6 metres at the base and was probably in the region of 25 metres high. We are told that the door was made of solid copper and bore the image of the god emerging  from the temple but of course it is long gone. Four flagstaffs—cedar poles topped with electrum or gold—were set up in grooves in the façade of the pylon. A set of stairs led to the roof of the structure and there were a couple of rooms in the thickness of the stonework. Similar rooms in later temples served as libraries, store rooms for ritual paraphernalia and robing rooms.

from the temple but of course it is long gone. Four flagstaffs—cedar poles topped with electrum or gold—were set up in grooves in the façade of the pylon. A set of stairs led to the roof of the structure and there were a couple of rooms in the thickness of the stonework. Similar rooms in later temples served as libraries, store rooms for ritual paraphernalia and robing rooms.

In front of it stood a pair of obelisks, the first to be erected at the site. They were of red granite from the quarries at Aswan and stood 22 metres high and weighed upwards of 1300 tonnes with tops encased in electrum. They were meant to honour the king’s jubilee (despite the shortness of his reign). Only one (left) still stands today.

The space between the two pylons, known as the Wadjet Hall, was described as an ‘august pillared hall with papyriform columns.’ Five column bases were found in the area, reused by Tuthmosis III, but they originally supported cedar columns for a wooden roof. This was later removed by Hatshepsut so that she could erect her two  obelisks. Recent excavations (Jean-François Carlotti & Luc Gabolde 2003) have revealed that Tuthmosis III’s remodelling had covered up niches along the inner face of Pylon IV containing Osiride statues of his grandfather. The statues that stand there now are not the originals, however, but were moved from the colonnade beyond Pylon V.

obelisks. Recent excavations (Jean-François Carlotti & Luc Gabolde 2003) have revealed that Tuthmosis III’s remodelling had covered up niches along the inner face of Pylon IV containing Osiride statues of his grandfather. The statues that stand there now are not the originals, however, but were moved from the colonnade beyond Pylon V.

There is a school of thought that holds that originally there was just a columned porch here and that Pylon IV was erected by Tuthmosis III. This would certainly have made the installation of the obelisks considerably easier. On the other hand, it raises questions about Tuthmosis I’s obelisks. It would suggest that the grandson erected them too and then set up a pair of his own in front of them. Its all a bit of a puzzle. One thing that is clear is the fact that henceforth this was considered the entrance to the temple ‘proper’ and it is the oldest part of the complex still standing.

Tuthmosis II (1518-1504 BC)

Tuthmosis I was succeeded by his son, Tuthmosis II, the son of a minor wife named Mutnofret. At the time, descent through the female line was every bit as important as the principal primogeniture if not more so, and it was decided when he became heir to the throne that he be given his half-sister, Hatshepsut, as his queen. She was the daughter of Tuthmosis I and his principal wife, Ahmose. On the death of Meritamun she evidently became the senior female of old royal line and succeeded her as God’s Wife of Amun.

According to Manetho, the new king reigned for a little over thirteen years but the latest date we have is from his first year and many scholars would reduce the number to three. There is little in the way of building activity to mark his reign—nothing at all in the  north of the country. There is no tomb nor funerary temple that can be identified with him although he may have begun work on the latter at Deir el-Bahri. On the other hand, he lived long enough to fight campaigns in both Nubia and the Sinai, and father two children—a daughter, Neferure, with Hatshepsut and a son, another Tuthmosis with a minor wife named Aset.

north of the country. There is no tomb nor funerary temple that can be identified with him although he may have begun work on the latter at Deir el-Bahri. On the other hand, he lived long enough to fight campaigns in both Nubia and the Sinai, and father two children—a daughter, Neferure, with Hatshepsut and a son, another Tuthmosis with a minor wife named Aset.

At Karnak, almost nothing of his work remains visible although his cartouche can be found on the buildings of his widow and his son and they work on them may have commenced under his authority. His most important project was the addition of a festival court to the front of Pylon IV, the main entrance to the temple, where the two principal axes of the complex intersected, one last resting place for the god before he set out on his journey south. The spot was later the site of the Third Pylon of Amenhotep III, who demolished the earlier work and used the blocks for its core. Most of these blocks came from a large pylon, similar in scale to Pylon IV and on the same east-west alignment. There was another, smaller pylon (‘Amun is the one who makes the Two Lands festive’) along the main axis to the south and three doorways leading away to the north.

Suggested Reading:

| Blyth, Elizabeth | 2006 | Karnak, The Evolution of a Temple |

| Dorman, Peter F. & Betsy M. Bryon | 2007 | Sacred Space & Sacred Function in Ancient Thebes. Studies in Oriental Civilization No. 61. Oriental Institute. University of Chicago |

| Strudwick, Nigel & Helen | 1999 | Thebes in Egypt |