There were as many as sixty festivals celebrated every year in Thebes but by far the largest and most important was the ‘Beautiful Feast of the Opet,’ which was held in honour of the great god Amun during the second month of Akhet, the season of the inundation. With the crops in and the countryside under water, the whole farming population of the district were free to participate in the festivities, the feasting and the spectacle. The events centred around fertility and renewal—renewal of the land, renewal of the pharaoh and (most importantly) renewal of the god. It involved a journey by both god and pharaoh from Karnak to the Luxor Temple and back again, a distance of about two kilometres.

Hatshepsut & Tuthmosis III worshipping Amun-Re (Karnak. La Chapelle Rouge)

The earliest known occurrence was during the reign of Hatshepsut, early in the New Kingdom period, but it may well have begun much earlier. Hatshepsut, as a woman, would have needed all the support she could muster—she had more or less usurped the throne from her stepson,  Tuthmosis III—and it is possible she took an existing ritual and dramatically increased its scale to emphasize her link with the god. In her day the celebrations lasted 11 days but, by the time of Ramesses II, they went on for a full three weeks.

Tuthmosis III—and it is possible she took an existing ritual and dramatically increased its scale to emphasize her link with the god. In her day the celebrations lasted 11 days but, by the time of Ramesses II, they went on for a full three weeks.

The Luxor Temple was also dedicated to Amun but, as it was thought to be the primeval mound of creation, the emphasis was more on his nature as Amun-Min, the fertility god, rather than as Amun-Re, the creator. The statue of the god Amun-Re was first bathed and then decked out in its finest array—colourful robes and magnificent jewellery of gold, and lapis lazuli. He was then placed into a small shrine of gilded wood, which was in turn placed on a portable barque. Accompanied by the high priests and with appropriate amount of fanfare, he was brought from the holy-of-holies, through the various columned halls and into the forecourt where members of the royal family and select representatives of the ordinary people were permitted to view the activities and verify that they were done properly. The statues of Mut and Khons awaited him, having been brought from their own temples in barques of their own. The pharaoh himself presided over the rites and ceremonies that preceded their departure and when these were complete the whole party set off for the Ipet Resyt (‘Southern Harem’) as the Luxor Temple was known.

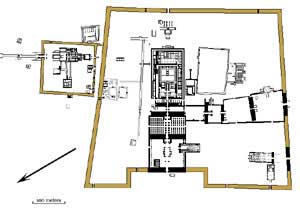

GoogleEarth View of the Processional Route

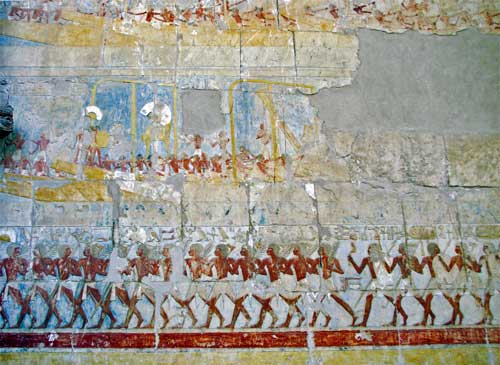

In Hatshepsut’s day, the procession went by land and turned left as it emerged from the temple building, exiting through the newly build Pylon VIII. The whole route was lined with cheering  multitudes as the god proceeded down the sphinx lined avenue. The wab-priests (‘purifiers’), with their shaven heads and bleached white linen robes, shouldered the burden of the three barques (left). They were accompanied by other priests wearing leopard skin mantles along with large numbers of fan-bearers, musicians, singers and acrobatic dancers. The spectacle would have been magnificent as the procession passed by, and the crowds delirious with joy. Along the way, Hatshepsut established six way stations where the priests could put down their burden and let a new group take it up. The last of these was just outside the entrance to the temple but was entirely rebuilt by Ramesses II and enclosed within his new courtyard.

multitudes as the god proceeded down the sphinx lined avenue. The wab-priests (‘purifiers’), with their shaven heads and bleached white linen robes, shouldered the burden of the three barques (left). They were accompanied by other priests wearing leopard skin mantles along with large numbers of fan-bearers, musicians, singers and acrobatic dancers. The spectacle would have been magnificent as the procession passed by, and the crowds delirious with joy. Along the way, Hatshepsut established six way stations where the priests could put down their burden and let a new group take it up. The last of these was just outside the entrance to the temple but was entirely rebuilt by Ramesses II and enclosed within his new courtyard.

The sphinx-lined approach to the Luxor Temple & the pylon of Ramesses II (1985)

Hatshepsut built extensively at Luxor but, unfortunately, none of her works have survived except as recycled stone used in later buildings. From what we know of the practice in later times, the gods would have been received in a large, open courtyard with the appropriate rituals and sacrifices after which they would be taken into the temple. Mut and Khons went to their individual  shrines while the pharaoh and Amun-Re went first to the Chamber of the Divine King and then on to the holy-of-holies with ceremonies being held in each. The pharaoh underwent ritual purification and a re-enactment of his coronation. Something of the power of the god was transferred to the royal ka, topping up the royal batteries so to speak. In return, the pharaoh, through offerings and the performance of such rituals as the Opening of the Mouth, set in motion a new cycle of creation and re-ignited the sacred spark within the god. The Sacred Marriage between Amun and Mut was re-consummated—with the pharaoh and his queen acting as stand-ins—and the divine pair took a few days honeymoon in the seclusion of the temple. This proper performance of this fertility ritual was absolutely vital to the continued good order of the universe and there was a strong erotic element to the proceedings. After the celebrations were over, the pharaoh and the three gods returned to Karnak—this time by boat.

shrines while the pharaoh and Amun-Re went first to the Chamber of the Divine King and then on to the holy-of-holies with ceremonies being held in each. The pharaoh underwent ritual purification and a re-enactment of his coronation. Something of the power of the god was transferred to the royal ka, topping up the royal batteries so to speak. In return, the pharaoh, through offerings and the performance of such rituals as the Opening of the Mouth, set in motion a new cycle of creation and re-ignited the sacred spark within the god. The Sacred Marriage between Amun and Mut was re-consummated—with the pharaoh and his queen acting as stand-ins—and the divine pair took a few days honeymoon in the seclusion of the temple. This proper performance of this fertility ritual was absolutely vital to the continued good order of the universe and there was a strong erotic element to the proceedings. After the celebrations were over, the pharaoh and the three gods returned to Karnak—this time by boat.

A boat procession from Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri

Hatshepsut’s festival lasted 11 days but in later times it was known to go on for as long as a month. It was a time of feasting and celebration for the people, with obvious political benefits for the pharaoh. The most notable change in the proceedings was that, from the time of Amenhotep III, the journey south was often made by boat. The statue of Amun-Re would stop at the temples of Mut and Khons and then the three of them would by carried down to the quay side where the portable barques would be loaded onto the real things. Gangs of men hauling on papyrus ropes dragged the vessels upstream, accompanied by chariots and infantry with their standards and pennants to the fore.