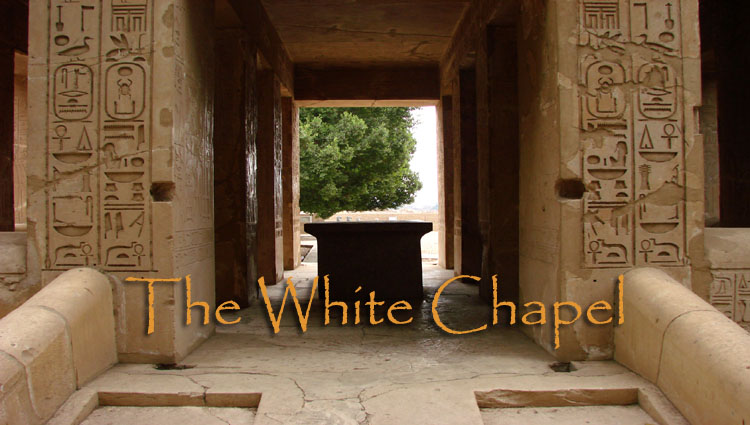

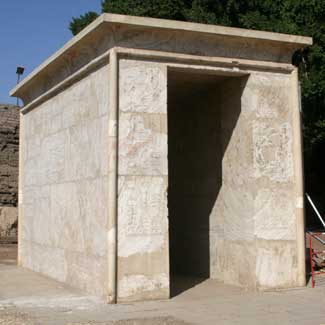

The White Chapel

Although virtually nothing stands of the Amun Temple of Senwosret I, by pure chance one of his other buildings, a real architectural jewel known as the White Chapel, can be seen in the Open Air Museum at  the site. The building had in fact been destroyed in antiquity but its carved stone blocks of Egyptian alabaster (calcite) were used as fill by the builders of the Third Pylon (Amenhotep III). In the course of restoration, the interior of the pylon was cleared by Henri Chevrier in the 1920s and nearly a thousand blocks belonging to at least eleven buildings were recovered. The blocks belonging to Senwosret’s building were easy to identify because of their exquisitely carved reliefs and inscriptions. When the puzzle was finally put together in 1940 the result was a small, open kiosk used by the pharaoh during his sed-festival, celebrated after 30 years on the throne to renew his power and potency.

the site. The building had in fact been destroyed in antiquity but its carved stone blocks of Egyptian alabaster (calcite) were used as fill by the builders of the Third Pylon (Amenhotep III). In the course of restoration, the interior of the pylon was cleared by Henri Chevrier in the 1920s and nearly a thousand blocks belonging to at least eleven buildings were recovered. The blocks belonging to Senwosret’s building were easy to identify because of their exquisitely carved reliefs and inscriptions. When the puzzle was finally put together in 1940 the result was a small, open kiosk used by the pharaoh during his sed-festival, celebrated after 30 years on the throne to renew his power and potency.

The building is an almost square (6.8 x 6.45 metres) platform with a shallow staircase with a central ramp at either end. Sixteen square and oblong pillars support a roof with a cavetto cornice,  a type of concave moulding decorated with leaves at the top of a wall. It is thought to imitate the overhang of a wall made of reed matting. The corners of the building have semi-circular torus roll moulding, which also imitates the architecture of a reed hut. The pillars around the outside are separated by low balustrades with rounded tops, creating a building that has a very open feel to it.

a type of concave moulding decorated with leaves at the top of a wall. It is thought to imitate the overhang of a wall made of reed matting. The corners of the building have semi-circular torus roll moulding, which also imitates the architecture of a reed hut. The pillars around the outside are separated by low balustrades with rounded tops, creating a building that has a very open feel to it.

Carved figures personifying the Nile and carrying the names of various districts and buildings founded by Senwosret decorated the two ends of the pavilion, on either side of the stairways, while the sides carried lists of the nomes of Upper and Lower Egypt along with some geographical information including records of the heights of the Nile flood. The emphasis is definitely on Amun’s role as owner/manager of the Land, who provides the life-giving waters that restore its fertility.

The pillars are decorated with relief work of exceptionally high quality, typical of the Senwosret’s works. Square peg holes can be seen in the stonework, most likely for the attaching sheets of hammered gold over some of it. On the outside, carved figures personifying the Nile and carrying  the names of various districts and buildings founded by Senwosret decorated the two ends of the pavilion, flanking the stairways, while the sides carried lists of the nomes of Upper and Lower Egypt along with some geographical information including records of the heights of the Nile flood. The emphasis is definitely on Amun’s role as owner/manager of the Land, who provides the life-giving waters that restore its fertility.

the names of various districts and buildings founded by Senwosret decorated the two ends of the pavilion, flanking the stairways, while the sides carried lists of the nomes of Upper and Lower Egypt along with some geographical information including records of the heights of the Nile flood. The emphasis is definitely on Amun’s role as owner/manager of the Land, who provides the life-giving waters that restore its fertility.

The central theme in the decoration of the pillars involves the pharaoh and Amun who takes the form of the fertility god Min. The god stands mummiform and with an enormous erection on top of a rectangular pedestal. He wears a double feather crown on his head and carries a flail, a symbol of kingship. Behind the god is a fenced enclosure with tall heads of romaine (or cos) lettuce, considered aparticularly potent aphrodisiac by the ancient Egyptians and thus a symbol of fertility. In other scenes, the god is in his more usual guise and offers the king, led by Re-Horakhty, the ankh symbol of life. The king is shown wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt, the Red Crown of the Delta or the double crown of all Egypt—rituals involving the pharaoh in all three roles were important parts of the sed-festival. In one scene (left) he offers a conical loaf of bread to Amun-Min in another, jars of perfumed oil.

other scenes, the god is in his more usual guise and offers the king, led by Re-Horakhty, the ankh symbol of life. The king is shown wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt, the Red Crown of the Delta or the double crown of all Egypt—rituals involving the pharaoh in all three roles were important parts of the sed-festival. In one scene (left) he offers a conical loaf of bread to Amun-Min in another, jars of perfumed oil.

There is some debate over the specific function of structure. At first it was assumed that it was a barque shrine, where the boat carrying the statue of the god would rest temporarily, and it has been restored with a pink granite pedestal of the appropriate height. However, the pedestal is inscribed with the names of Amenemhat III and Amenemhat IV who reigned a century or more after Senwosret. Although it may have been converted into a barque shrine at this time, its original function is indicated by the emplacement in the paving slabs for a double throne, one for the king (or a statue of the king) in each of his aspects. Around the central pillars were sockets in the floor and ceiling for a screen to lend a little privacy.

central pillars were sockets in the floor and ceiling for a screen to lend a little privacy.

According to the inscriptions that decorate its pillars, it was originally located in an enclosure known as the ‘High Lookout of Kheperkare.’ No one knows for certain where the enclosure was except that it was undoubtedly nearby, probably just outside the entrance to the compound. However, there is good evidence to suggest that the earliest version of the Luxor Temple was already in existence and so it is possible that the second approach from the north was too, giving two possible locations for the building.

Other Monuments

A much better candidate for one of Senwosret’s barque shrines was recovered in fragments in the fill of one of the pylons. Its decoration and ground plan is very similar to well-documented later examples, such as the one belonging to Amenhotep I (below left) that now stands in the Open Air Museum. The building was made out of  Tura limestone and measures 4.4 x 3.2 metres. There are entrances at both ends, which would have been fitted with double-leaved doors—either bronze or gilded wooden panels. The roof had a cavetto cornice and there was torus moulding at the corners. Unlike the New Kingdom versions, which had solid walls, this one had a small window on either side. The reliefs that decorated the shrine both inside and out were badly damaged during the reign of Akhenaten but enough survives to reconstruct some scenes. One on the inside wall shows Senwosret in front of the sacred barque, perhaps pouring out a libation.

Tura limestone and measures 4.4 x 3.2 metres. There are entrances at both ends, which would have been fitted with double-leaved doors—either bronze or gilded wooden panels. The roof had a cavetto cornice and there was torus moulding at the corners. Unlike the New Kingdom versions, which had solid walls, this one had a small window on either side. The reliefs that decorated the shrine both inside and out were badly damaged during the reign of Akhenaten but enough survives to reconstruct some scenes. One on the inside wall shows Senwosret in front of the sacred barque, perhaps pouring out a libation.

Like the White Chapel, the barque shrine was built for Senwosret’s first sed-festival. It stood until the days of Horemheb, the last of the pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty, when it was dismantled and used in the core of Pylon IX. This would seem to suggest that it originally stood somewhere in the immediate vicinity, most likely along the southern approach to the temple.

Another small building belonging to Senwosret I is black granite naos dedicated to Amun that was found in the court of Pylon VIII. It was carved from a single block of stone and measured a little under a metre square and stood 1.75 metres high (it looks more or less like sentry box with a cavetto cornice). The outside was decorated with reliefs of the pharaoh greeting the Amun and there were inscriptions down each side of the door. In the reliefs, Senwosret faces the door wearing the southern crown on the right side and the northern crown on the left, suggesting that the monument originally faced east, probably along the southern approach. The fact that the pharaoh faces outwards means that the naos probably held a statue of him rather than the god.