The Temples

The prehistoric temples of Malta are among the earliest free-standing stone buildings in the world. The first ones date to about 3600 BC—long before the Egyptians began to build in stone and nearly a thousand years before the pyramids—and the phenomenon lasted until around the end of the millennium.

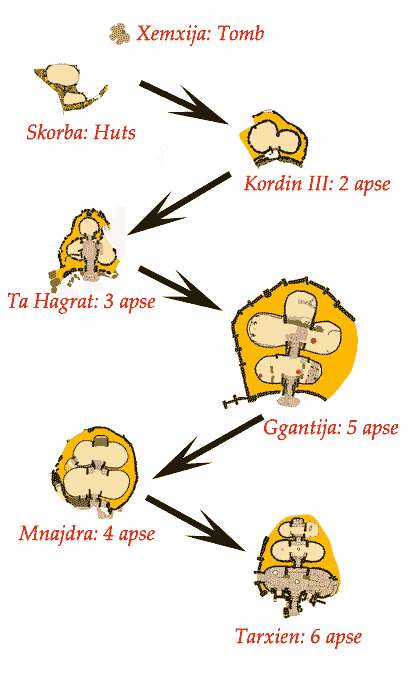

Archaeologist have long pondered the question of what inspired the form of the temples. There was undoubtedly some sort of relationship between the lobed chambers found in some of the rock-cut tombs and the arrangement of rooms in the temples. Unfortunately, the dating evidence is not precise enough to indicate which came first and it is just as easy to  claim that the tombs were inspired by the temples as the reverse. Another likely source of inspiration lies in pre-temple domestic architecture, such as the oval huts found at Skorba. The deposit in one of these contained terracotta figurines and goat skulls, suggesting that it may have served as a shrine of sorts. However, no intermediary stage in the development has yet been found—it goes straight from the very simple to the very complex.

claim that the tombs were inspired by the temples as the reverse. Another likely source of inspiration lies in pre-temple domestic architecture, such as the oval huts found at Skorba. The deposit in one of these contained terracotta figurines and goat skulls, suggesting that it may have served as a shrine of sorts. However, no intermediary stage in the development has yet been found—it goes straight from the very simple to the very complex.

Temples are most often found in pairs and sometimes even in threes and fours. Furthermore, these smaller complexes seem to cluster—around the head of the Grand Harbour, the Marsaxlokk Harbour on the east coast and the Xaghra plateau on Gozo for example (above right). The complexes at Hagar Qim and Mnajdra are less than half a kilometre apart. Colin Renfrew believes that these larger groupings reflect the territory of particular groups, seeking a sense of self-identity through shared beliefs and rituals.

The Temple Building

A typical temple (if there is such a thing) is a symmetrical arrangement of rooms along a single axis. There was a monumental doorway that looked out onto a curved forecourt where the community could assemble. The interior was made up of a number of semi-circular apses and a central altar at the rear of the building. The earliest temples are trefoil, that is to say they have a cloverleaf layout, but later examples can be much more elaborate. Access to the interior was restricted. The outer apses, which may have been unroofed, could accommodate no more than a small group of individuals. There were V-shaped perforations in some door jambs leading to the heart of the building that were obviously intended to fasten some sort of door, which was then secured by a bar. The usual interpretation is that secret rites were performed here by a religious elite on behalf of the whole community.

The forecourt was clearly meant to be a place of assembly. It was carefully levelled and often paved with torba (a layer of crushed Globigerina on a rubble base, which was then repeatedly wetted down and pounded until it was hard enough to polish) or flagstones—a perfect dance floor. The focus of attention was the entrance to the temple set in the middle of a curved façade that seemed to enclose the space in front of it.

Mnajdra.Façade and Forecourt of the Temple

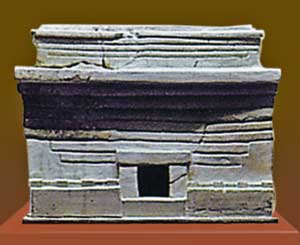

The façade was made up of large upright stones (orthostats) that were graded in height so that the tallest ones were at the extremities. Sometimes there was a low bench in front it, perhaps designed for the display of statues or other cult objects. Above the orthostats were a number of courses of smaller stone blocks, laid in horizontal courses, as shown in the graffito found at Mnajdra and the fragmentary model from Tarxien. The effect must have been powerful (especially at night, with torches blazing) with the façade towering over the courtyard.

|

Model Temple from Tarxien Model Temple from Tarxien |

In some cases, the side and rear external walls were also made of orthostats, arranged in a pattern of alternating faces and edges and topped with a number of horizontal courses of smaller blocks— that seems to be the case in the better preserved examples, at any rate.

Ggantija. Outer Wall of the Temple

The entrance to the temple was framed by a pair of orthostats capped by a massive stone lintel, to form what is known as a trilithon. Generally there was more than one set, creating a short entrancepassage. A good example survives at the site of Ta Hagrat (below right). Immediately  inside therewas often a small courtyard area—this was especially true of the earlier, trefoil examples— which may or may not have been open to the sky. The court, if there was one, was flanked by a pair of D-shaped chambers or apses that contained altars and other cult installations. As time went on the number of apses was increased from a single pair to two or even three pairs. The terminal chamber was originally the main focus of ritual activity but finally the builders decided to do away with it and replace it with an elaborate niche.

inside therewas often a small courtyard area—this was especially true of the earlier, trefoil examples— which may or may not have been open to the sky. The court, if there was one, was flanked by a pair of D-shaped chambers or apses that contained altars and other cult installations. As time went on the number of apses was increased from a single pair to two or even three pairs. The terminal chamber was originally the main focus of ritual activity but finally the builders decided to do away with it and replace it with an elaborate niche.

The interior wall faces were either smooth Globigerina or Coralline orthostats with a coat of plaster that was often painted with red ochre, traces of which have been found at a number of sites. Here too, the upper part of the wall was made up of smaller blocks of stone often laid in overlapping courses that gradually reduce the span of the ceiling—a technique known as corbelling. The space between the inner and outer faces of the walls was filled with rubble of earth and stone—often containing cultural material—but in some cases there was room enough for additional  chambers, accessed by doorways or portholes. Floors were paved with flagstones or covered with torba.

chambers, accessed by doorways or portholes. Floors were paved with flagstones or covered with torba.

The problem of how the temples were roofed is still unresolved. A model found at Ta’ Hagrat (left) would seem to indicate that long stone slabs were laid across the building. The scale of the model suggests they were of massive size and the evidence from sites like Mnajdra and Hagar Qim shows that the builders used a technique known as corbelling (arranging the blocks in the upper part of the wall so that each course slightly overlaps the one below) to reduce the amount of space that needed to be covered. Unfortunately, no such slabs or even broken pieces of them have survived at any of the excavated sites. Of course they may well have been removed by later farmers and broken up for building material but it is odd that the destruction would have been so complete. On the other hand, at Skorba East a layer of charcoal was found in the fill above the floor of the temple and this has been interpreted as the remains of the roof, probably made out of brushwood and packed clay supported by wooden rafters. It has been suggested that the paved areas found at a number of sites were open to the sky, meaning that only the apses had roofs.

Furnishings

Most temples were provided with interior furnishings, generally interpreted as altars, which were usually placed at the rear of the apse. Many of these are simple blocks of stone, often decorated with pitting or reliefs in vegetal or animal motifs. There are also trilithon altars similar to the doorways but (normally) on a smaller scale. Some are as tall as 2.5 metres, however, which is an awkward height for offerings and sacrifices. The one shown (right) is a reproduction that now sits outdoors, at the site of Tarxien. The original is in the National Museum in Valletta.

Most temples were provided with interior furnishings, generally interpreted as altars, which were usually placed at the rear of the apse. Many of these are simple blocks of stone, often decorated with pitting or reliefs in vegetal or animal motifs. There are also trilithon altars similar to the doorways but (normally) on a smaller scale. Some are as tall as 2.5 metres, however, which is an awkward height for offerings and sacrifices. The one shown (right) is a reproduction that now sits outdoors, at the site of Tarxien. The original is in the National Museum in Valletta.

Double-decker altars have also been found, with a central pillar  resting on a trilithon and supporting a horizontal slab. Finally, there are carved pedestals (some elaborately so) standing about a metre high that support shallow basins (left). At Hagar Qim, one of the apses contains a round-topped cylindrical pillar about a metre and a half high. In later times, these were known as baetyls and were found all over the Mediterranean world in Classical times. A square sectioned version stands in its own little shrine, built into the outer wall of the temple. Baetyls were used to represent the deity when a true depiction would have been wrong for whatever reason, and that certainly looks like the case here.

resting on a trilithon and supporting a horizontal slab. Finally, there are carved pedestals (some elaborately so) standing about a metre high that support shallow basins (left). At Hagar Qim, one of the apses contains a round-topped cylindrical pillar about a metre and a half high. In later times, these were known as baetyls and were found all over the Mediterranean world in Classical times. A square sectioned version stands in its own little shrine, built into the outer wall of the temple. Baetyls were used to represent the deity when a true depiction would have been wrong for whatever reason, and that certainly looks like the case here.

There were undoubtedly fittings and furnishings made out of perishable, organic materials— carpets or hangings—but these have not survived.

Construction

Once a suitable site was chosen—preferably one that was reasonably level and unencumbered. It there was a supply of good stone nearby, so much the better. Coralline limestone can be found in many parts of the islands already cracked into suitable blocks. It is hard but brittle and could  easily be split into slabs or blocks using wedges. Globigerina is much softer and it is relatively easy to cut to the right shape. Whichever stone was used depended on local availability—Tarxien and Hagar Qim (right) were built entirely out of Globigerina (despite the fact that it was much more prone to weathering). However, even if Corallines were the principal stones used, Globigerinas were necessary for some of the internal fittings such as doorways or altars that needed to be more carefully carved.

easily be split into slabs or blocks using wedges. Globigerina is much softer and it is relatively easy to cut to the right shape. Whichever stone was used depended on local availability—Tarxien and Hagar Qim (right) were built entirely out of Globigerina (despite the fact that it was much more prone to weathering). However, even if Corallines were the principal stones used, Globigerinas were necessary for some of the internal fittings such as doorways or altars that needed to be more carefully carved.

The stone blocks, some of which weighed several tonnes, were probably moved by means of sledges and the so-called ‘cart tracks’ (below left) found in many parts of the island may well have been for their rails. It has been suggested that the Globigerina spheres found at Tarxien were used to move blocks of stone, but they would have been far too soft to support their weight over any distance. The blocks were apparently manoeuvred into their final position using levers—many of the uprights have notches at their base where the pole would have been inserted. Ramps of earth and rubble were most likely used to raise the lintels.

likely used to raise the lintels.

The number of people needed would have been relatively small—space on the building site would have been limited. The transportation and erection of some of the larger stones would have required a fair amount of muscle power, but this may well have been provided by oxen. Enigmatic cart tracks have been found in the south of the island and these may have had something to do with the transportation of the stone.

Most of the hard work would have been on the interior, where the workspace would have been very restricted and the size of the stones such that they could be handled by a single worker. Working during the agricultural off-season, say three months out of the year, a temple could have quite easily erected in a few years (3-5) with a workforce numbering in the dozens.

Sequence

A sequence has been worked out by John Evans, who believed that the temples evolved out of more developed rock cut tombs such as those at Xemxija which have lobe-shaped chambers. However, other scholars, such as Anthony Pace, question whether the chronology is secure enough  to determined which one influenced the other. Evans’ scheme is shown (right).

to determined which one influenced the other. Evans’ scheme is shown (right).

The trefoil temple is essentially a more formally designed version of the original type. Subsequently, it was made more elaborate by the addition of an outer pair of apses. The simplest explanation for this is that they needed more interior space to deal with changes in the cult activity that went on there. In a number of instances, there is evidence for a doorway or screen to separate the outer apses from the interior, dividing the temple into a relatively public area and one that was probably restricted to priests or the like. In time the innermost chamber was reduced to a vestigial niche and altar, reducing the number of apses to four. Finally, a unique building with three pairs of apses was built at Tarxien.

The archaeological evidence supports Evans’ sequence. At Ggantija, the four apse North Temple is demonstrably later than the five apse South Temple since the outer wall of the latter was rebuilt to accommodate it. Similarly, at Tarxien the six apse temple was clearly inserted between the two earlier four apse temples, which were drastically modified to accommodate it. It is now seems clear that, rather than a steady and gradual development, there were a couple of fairly brief episodes of temple building—the Ggantija phase (around 3500 BC) and the Tarxien period some 500 years later. At each site the evidence indicates clearly that the temples were built successively, but that the construction of one did not mean the abandonment or destruction of its predecessor—although the nature of its function may have changed.

Orientation

There is good evidence to suggest that the inhabitants of Malta and Gozo were very interested in astronomy. The position of the stars enabled them to navigate and plot the rhythms of the farming  year. A broken limestone slab from the Tal-Qadi Temple (left) has what certainly appears to be a representation of the heavens, showing the moon and stars as well as a number of radiating lines dividing it into quadrants. Recent surveys of the monuments have revealed that quite a number of them were oriented towards a significant celestial event—sunrises, sunsets and the heliacal rising of certain stars, for example. Of course, the stars are not fixed in the heavens and the earth wobbles a bit on its axis, so things have changed a lot in the past 5,000 years. You have to be certain exactly when the temple was built to know what the sightlines were at the time. In addition, with all of the activity going on in the night sky it is quite possible that it all boils down to coincidence. The builders had a clear preference for the quadrant running from the southeast to the southwest and the majority of temples face that direction. This might have something to do with the mid-winter sunrise or sunset but it is equally plausible that they wanted to maximize the amount of light available.

year. A broken limestone slab from the Tal-Qadi Temple (left) has what certainly appears to be a representation of the heavens, showing the moon and stars as well as a number of radiating lines dividing it into quadrants. Recent surveys of the monuments have revealed that quite a number of them were oriented towards a significant celestial event—sunrises, sunsets and the heliacal rising of certain stars, for example. Of course, the stars are not fixed in the heavens and the earth wobbles a bit on its axis, so things have changed a lot in the past 5,000 years. You have to be certain exactly when the temple was built to know what the sightlines were at the time. In addition, with all of the activity going on in the night sky it is quite possible that it all boils down to coincidence. The builders had a clear preference for the quadrant running from the southeast to the southwest and the majority of temples face that direction. This might have something to do with the mid-winter sunrise or sunset but it is equally plausible that they wanted to maximize the amount of light available.