Prehistoric Settlement

The islands were first occupied by about the end of the Sixth Millennium BC—radiocarbon dates calibrating to about 5000 BC were recovered from material found alongside a wall at the early settlement at Skorba. From the start the settlers were fully agricultural—there is no sign of any previous hunting and gathering activity. The plants and animals on which they were dependant— various cereal crops along with sheep, goat, cattle and pigs—were not native to the islands and must have arrived with the settlers. A long sea voyage in small, open boats or rafts would have been a daunting proposition in those days, especially when transporting livestock, but not impossible. By about 8000 BC, the inhabitants of mainland Greece were acquiring obsidian from the island of Melos, which must have involved a sea voyage of at least 100 km—roughly the same distance as between Malta and Sicily.

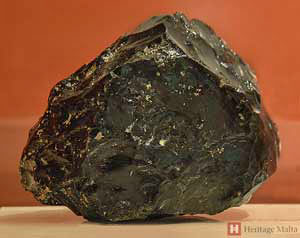

The earliest pottery on Malta consists of an impressed ware that was virtually identical that used in Sicily. Evidently overseas contacts were maintained throughout the Neolithic—obsidian from the Lipari Islands, to the north of Sicily, and from Pantelleria, an island lying between Sicily and Tunisia, occur regularly in the archaeological record.. However, the amounts involved were quite small and contact seems to diminish with time. Left largely to themselves, their culture developed along very idiosyncratic lines, to say the least.

Ghar Dalam

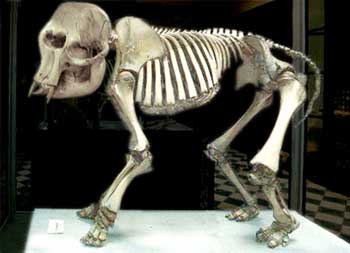

The cave of Ghar Dalam on the slopes of a valley running down to what is now the container port of Birzebbuga at the south-eastern end of Malta. Because of in washed silt, it is impossible to say how far into the hillside it goes but it is at least 144 metres long. It was formed by water percolating  through and dissolving the Lower Coralline limestone during the Pleistocene, perhaps half a million years ago. Periodic flooding washed material into the cave and excavations conducted over the past 100 years or so have distinguished six principal layers. The lowest was a deposit of clay 125 cm thick containing impressions of plant material but no bone. The layer above that, however, was rich in faunal remains and included some very exotic species. Most abundant were the bones of a species of pigmy hippopotamus (Hippopotamus melitensis) but there was also a pigmy elephant (Elephas falconeri) as well as both giant dormice (giant only in dormouse terms) and swans. Of course, the swans would have had no problem getting to Malta but the other species must have arrived when the islands were linked to Sicily and North Africa by a land bridge and were stranded there when sea-

through and dissolving the Lower Coralline limestone during the Pleistocene, perhaps half a million years ago. Periodic flooding washed material into the cave and excavations conducted over the past 100 years or so have distinguished six principal layers. The lowest was a deposit of clay 125 cm thick containing impressions of plant material but no bone. The layer above that, however, was rich in faunal remains and included some very exotic species. Most abundant were the bones of a species of pigmy hippopotamus (Hippopotamus melitensis) but there was also a pigmy elephant (Elephas falconeri) as well as both giant dormice (giant only in dormouse terms) and swans. Of course, the swans would have had no problem getting to Malta but the other species must have arrived when the islands were linked to Sicily and North Africa by a land bridge and were stranded there when sea- levels rose again. One possible scenario is that they arrived as normal sized individuals but, in the absence of natural predators, natural selection worked in favour of smallness (smaller animals being more energy efficient).

levels rose again. One possible scenario is that they arrived as normal sized individuals but, in the absence of natural predators, natural selection worked in favour of smallness (smaller animals being more energy efficient).

The elephants and hippos apparently died out at some time around 180,000 BP an event marked in the cave by a pebble layer 35 cm thick. The fauna that were present in the layer above the pebbles was entirely different than previously. There was a species of small deer, derived from the Red Deer (Cervus Elephas) found on the European mainland. There were also a few carnivores such as brown bear, wolf and red fox but no sign of any people at this point (approximately 18,000 years ago). Next there is a thin calcareous lens, not even a centimetre thick, and it is only above that that you finally get the kind of cultural debris that humans leave lying around—flint tools, potsherds, amulets, etc. This is mixed with the bones of domestic animals—sheep, goat and cattle.

Chronology

Unfortunately, almost all of the monuments under discussion were excavated long before the introduction of radiocarbon dating in the 1950’s, some of them as early as the beginning of the 19th century. Their relative chronology—the order in which they were built—could be established using traditional methods. These relied almost exclusively on changing styles of pottery—their form, fabric and decoration—and their stratigraphic position in well-recorded excavations. Absolute dating was pretty much a matter of guesswork until the radiocarbon revolution. Radiocarbon dates taken from more recently excavated sites with similar pottery has enabled us to pin down the chronology in more absolute terms. We now know that the Maltese Neolithic covered a period of nearly 3,000 years, from about 5200-2500 BC.

The pottery sequence was devised by John D. Evans in the 1950’s and refined by David Trump in the 1960’s. The material seems to fall into three major cycles, each marked initially by strong foreign influences but quickly settling into a strictly local development. The simplest explanation is to attribute these influences to the arrival a fresh immigrants from Sicily. Each phase is named after the site where it was first discovered or is best represented.

PERIOD |

POTTERY STYLE |

DATES |

|

EARLY NEOLITHIC |

Ghar Dalam | c. 5200-4500 BC | |

| Grey Skorba | c. 4500-4400 BC | ||

| Red Skorba | c. 4400-4100 BC | ||

TEMPLE PERIOD |

Zebbug | c. 4100-3700 BC | |

| Mgarr | c. 3800-3600 BC | ||

| Ggantija | c. 3600-3200 BC | ||

| Saflieni | c. 3300-3000 BC | ||

| Tarxien | c. 3150-2500 BC | ||

EARLY BRONZE AGE |

Tarxien Cemetery | c. 2400-1500 BC | |

Neolithic Pottery Styles

Early Neolithic

The pottery of the first settlers is known as Ghar Dalam Ware, after the cave site where it was first discovered. It is characterized by impressions around the rim and  neck of rather simple bowls and globular jars. This type of decoration links it directly with the Stentinello Ware of Sicily and, more generally, with the larger family of Impressed Wares found throughout the central and western Mediterranean. The connection with the homeland was soon lost, however, and the succeeding Grey Skorba Phase is dominated by rather plain vessels. This is succeeded by Red Skorba Ware (left), which was slipped (dunked in a thin solution of clay and water) and then burnished to a bright red sheen. The fabric is different and there is more variety in the shapes that were utilized—a type of ladle with a tall forked handle rising from the rim is fairly common. In some ways the pottery is similar to the Diana Ware found on Sicily but it may be coincidental.

neck of rather simple bowls and globular jars. This type of decoration links it directly with the Stentinello Ware of Sicily and, more generally, with the larger family of Impressed Wares found throughout the central and western Mediterranean. The connection with the homeland was soon lost, however, and the succeeding Grey Skorba Phase is dominated by rather plain vessels. This is succeeded by Red Skorba Ware (left), which was slipped (dunked in a thin solution of clay and water) and then burnished to a bright red sheen. The fabric is different and there is more variety in the shapes that were utilized—a type of ladle with a tall forked handle rising from the rim is fairly common. In some ways the pottery is similar to the Diana Ware found on Sicily but it may be coincidental.

Temple Period

The appearance of Zebbug Ware towards the end of the Fifth Millennium BC marks a major break with tradition and probably represents a further influx of people. There is  absolutely no continuity in fabric, shape or decoration and it seems to have its roots in Sicily once again. Decoration is prolific, if somewhat sloppily applied, and includes painted designs (red on a cream coloured slip) and grooves infilled with white paste (right) as well as incised patterns—including some anthropomorphic designs. There is continuity in many other aspects of the local culture (the architecture and sculpture, for example—that suggests the original occupants survived the process to a greater or lesser degree.

absolutely no continuity in fabric, shape or decoration and it seems to have its roots in Sicily once again. Decoration is prolific, if somewhat sloppily applied, and includes painted designs (red on a cream coloured slip) and grooves infilled with white paste (right) as well as incised patterns—including some anthropomorphic designs. There is continuity in many other aspects of the local culture (the architecture and sculpture, for example—that suggests the original occupants survived the process to a greater or lesser degree.

Mgarr Ware is essentially a continuation of the trends introduced in the previous phase but the pottery is much darker, having been fired in a reducing atmosphere. The difference may be purely functional—kitchenware as opposed to dinner service. In any event, the fabric of the pottery in the following Ggantija Phase is identical but the shapes are more varied and there is more decoration. The designs were generally scratched in after firing and were designed to hold a red ochre paste. It was during this period that the first temples suddenly appeared. Further developments take place in the Saflieni Phase but the great explosion of creativity comes with the Tarxien Phase, the grand finale of the temple-building period. There is an enormous range of shapes, including several new ones such as pedestalled bowls, biconical bowls (left), and amphorae.

but the great explosion of creativity comes with the Tarxien Phase, the grand finale of the temple-building period. There is an enormous range of shapes, including several new ones such as pedestalled bowls, biconical bowls (left), and amphorae.

The end of the Temple Age, which occurred around 3500 BC, was apparently sudden and complete. The material culture is entirely new—new styles of pottery and the introduction of metal objects. Temples were no longer built (they remained in use but served an entirely different purpose) and the dead were cremated rather than buried in collective tombs. The mechanisms by which these changes occurred is unknown—invasion and bloody murder is only one of a number of options.

Settlement

Unfortunately, although formal and ceremonial sites such as temples and cemeteries have survived reasonably well in Malta, settlements have proved elusive. What evidence we do have, apart from the material that has survived at Ghar Dalam, comes from sites that were later occupied by temples. Generally speaking, the evidence is indirect—household rubbish such as pottery, tools, charcoal, etc.—rather than architecture. The best comes from Skorba, where there seems to have been a considerable period of strictly domestic occupation before the construction of the temple. Excavations, conducted by David Trump from 1960-63, uncovered over 2 metres of deposit with a pottery sequence ranging from the Ghar Dalam to Ggantija phases. Radiocarbon dates indicate the site was occupied for a period of some 1,500 years.

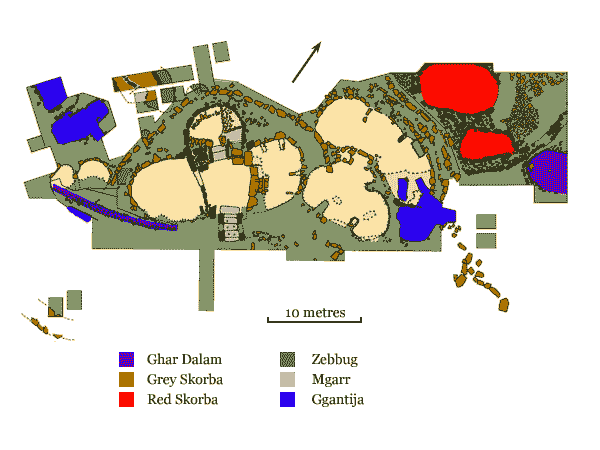

Plan of Skorba

The earliest building was a small, oval hut about 6 metres long associated with Ghar Dalam sherds—only the clay floor and partial traces of the surrounding wall have survived subsequent ploughing. Also associated with early domestic rubbish was an 11 metre long stretch of stone wall that is too big to belong to a house and may have been part of an enclosure wall (unfortunately, it runs under the later temple). Two adjacent rooms were uncovered just to the east of the temples—they were oblong (8.4 x 5.4 metres; 5.6 x 3.2 metres) and were enclosed within solid masonry. The interior was filled with grey clay—the disintegrated mud brick from the upper parts of the walls. There were cobbled spaces to the east and west but no hearths or other domestic furnishings. The presence of figurines and goat skulls suggest the building was a shrine, ancestral to the later temples.

Subsistence & Exchange

The material from Skorba included grains of cultivated barley, emmer and club wheat along with lentils. Flint sickle blades and food processing equipment such as querns and rubbing stones have  also been recovered. All of the animal bones recovered from the site belonged to domesticated species. Sheep and/or goat (species difficult to distinguish in an archaeological context) were the most common but cattle were also present in significant numbers as were pigs (both of which are shown in reliefs from Tarxien. No wild animals were represented in the assemblage—the larger species had probably been exterminated much earlier. Although mollusc shells have been found elsewhere, no fish bones were recovered from the site— despite the fact that Malta is entirely surrounded by water. However, flotation, a technique designed to recover micro artefacts such as these, was not used in the early 1960’s. Indirect evidence that fish may have been part of the diet can be found in a relief carving found at the temple at Bugibba. Spindle whorls have also been recovered, so we know that yarn

also been recovered. All of the animal bones recovered from the site belonged to domesticated species. Sheep and/or goat (species difficult to distinguish in an archaeological context) were the most common but cattle were also present in significant numbers as were pigs (both of which are shown in reliefs from Tarxien. No wild animals were represented in the assemblage—the larger species had probably been exterminated much earlier. Although mollusc shells have been found elsewhere, no fish bones were recovered from the site— despite the fact that Malta is entirely surrounded by water. However, flotation, a technique designed to recover micro artefacts such as these, was not used in the early 1960’s. Indirect evidence that fish may have been part of the diet can be found in a relief carving found at the temple at Bugibba. Spindle whorls have also been recovered, so we know that yarn was spun—coarse wool was available and, perhaps, some sort of vegetable fibre such as flax (linen).

was spun—coarse wool was available and, perhaps, some sort of vegetable fibre such as flax (linen).

The evidence indicates an economy based on mixed farming, probably at a subsistence level, with each family supplying its own needs with a little surplus for social obligations and bartering. Each family also probably produced their own pottery and manufactured their own bone or stone tools. They did not live in total isolation, however. A number of exotic materials found on the islands had to have been imported, including obsidian (right) and pumice from the Lipari Islands along with high quality flint and red ochre from Sicily. There is even the odd sherd of Sicilian pottery, probably from a container for some perishable material. None of these items could be classified as vital necessities and there value was probably symbolic, intended to cement social arrangements through the exchange of gifts. What the Maltese gave in return is unknown.

Belief Systems

Evidence from the pre-temple period that sheds any light on belief systems is very scarce. Mention has already been made of the possible shrine at Skorba, which dates to the last half of the  fourth millennium BC, with its goat horns and figurines. None of the figurines was intact but they seem to depict a female figure with swollen hips, minimal breasts and a very schematic head, such as in the baked clay example (left). They are apparently naked, with only what appears to be a girdle around the waist and some incised lines that probably represent necklaces—looking very much like the ‘mother-goddess’ whose image is found throughout the much of the Mediterranean world. The early farmers were very concerned with matters of fertility and fecundity (sex and reproduction) and saw the world in those terms. The figurines represent the female half of the equation with the male principle turning up in the stone phalli found elsewhere—at least, that is the case during the Temple Period.

fourth millennium BC, with its goat horns and figurines. None of the figurines was intact but they seem to depict a female figure with swollen hips, minimal breasts and a very schematic head, such as in the baked clay example (left). They are apparently naked, with only what appears to be a girdle around the waist and some incised lines that probably represent necklaces—looking very much like the ‘mother-goddess’ whose image is found throughout the much of the Mediterranean world. The early farmers were very concerned with matters of fertility and fecundity (sex and reproduction) and saw the world in those terms. The figurines represent the female half of the equation with the male principle turning up in the stone phalli found elsewhere—at least, that is the case during the Temple Period.

The sense of community was strongly felt and when someone died they joined their ancestors in a community of the dead, further strengthening the sense of permanence and of a connection to the landscape. In an island setting, there is a limited amount of land available and a strong sense of group identity is essential. Burials were collective with little to distinguish one individual from another. Rock cut tombs were the norm and were easy to carve, given the nature of the stone. The best-preserved of these was at Xaghra (below right) where a tomb of the Zebbug Period was excavated in 1988. A shaft 70 cm long led straight down to a pair of oval chambers. The remains of 65 individuals (54 adults and 11 children) were found—the bones of earlier interments pushed  aside to make way for new ones who were laid out intact until the flesh decomposed. The bones were liberally sprinkled with red ochre—symbolic of blood and life—a material that had to be imported from Sicily. The burials were accompanied by grave goods consisting of decorated pots (mainly from the Zebbug phase but some as late as Ggantija) and personal ornaments. The pots were almost all broken, the remains of food offerings or funeral meals, while the ornaments consisted of shell beads and pendants along with sixteen miniature stone axes and six V-perforated buttons. Just inside the entrance to one of the chambers the excavators found a stone block with a somewhat crude carving of a human face on it. Presumably it was intended to stand guard over the spirits of the dead.

aside to make way for new ones who were laid out intact until the flesh decomposed. The bones were liberally sprinkled with red ochre—symbolic of blood and life—a material that had to be imported from Sicily. The burials were accompanied by grave goods consisting of decorated pots (mainly from the Zebbug phase but some as late as Ggantija) and personal ornaments. The pots were almost all broken, the remains of food offerings or funeral meals, while the ornaments consisted of shell beads and pendants along with sixteen miniature stone axes and six V-perforated buttons. Just inside the entrance to one of the chambers the excavators found a stone block with a somewhat crude carving of a human face on it. Presumably it was intended to stand guard over the spirits of the dead.