Apollo & Delphi

According to one of the Homeric Hymns to Apollo, the god was born on the island of Delos in the Cyclades and set out from there to make his way in the world, looking for a place to make his home until finally he arrived at Mount Parnassos:

...here I am minded to make a glorious temple, an oracle for men, and hither they will always bring perfect hecatombs [sacrifices, normally of 100 cattle], both those who live in rich Peloponnesus and those of Europe and all the wave-washed isles, coming to seek oracles. And I will deliver to them all counsel that cannot fail, giving answer in my rich temple.

Homeric Hymn to Pythian Apollo

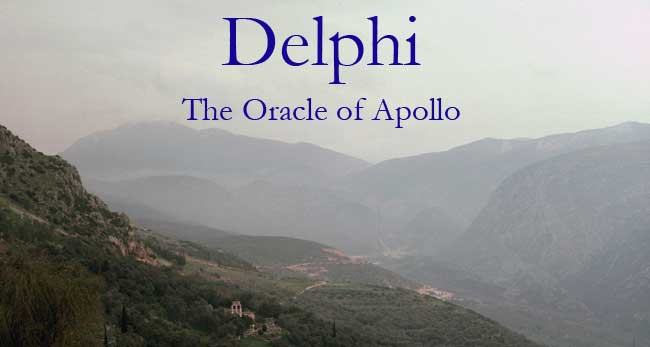

It is little wonder that he chose this particular site for there is none more spectacular in all of Greece. It is nestled in a broad cleft on the south slopes of Mount Parnassos, under the twin cliffs, known as the Phaedriadhes (“the Bright Ones”), which glow red when they catch the rays of the setting sun. There are magnificent views in all directions and, with the peak of mountain looming up behind, it is an enormous natural theatre.

It is little wonder that he chose this particular site for there is none more spectacular in all of Greece. It is nestled in a broad cleft on the south slopes of Mount Parnassos, under the twin cliffs, known as the Phaedriadhes (“the Bright Ones”), which glow red when they catch the rays of the setting sun. There are magnificent views in all directions and, with the peak of mountain looming up behind, it is an enormous natural theatre.

The name comes from delphus, ancient Greek for “womb.” The rock is mainly limestone and there are a number of springs that well up at the base of the mountain. Although the surrounding landscape was pretty barren, it was the site of a fairly substantial settlement during the Late Bronze Age (the last half of the second millennium BC). The reason for this is probably the fact that it lies close to the Gulf of Corinth and sits right on the principal east-west route across central Greece. The main road follows a rather narrow and tortuous path, hugging the lower slopes as it winds its way through the mountains (as anyone who took the bus in the old days can testify). It can be quite dry and dusty, especially in the summer time and the deliciously cool springs and shady glades of Delphi must have been a welcome sight for the traveller. The ancients looked upon springs as magical places with power to heal the sick and give inspiration to poets—healing and poetry (along with prophecy) were among the special provinces of Apollo.

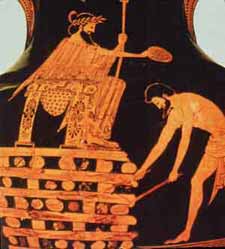

Unfortunately, the site was already sacred to the earth-goddess Gaia (Ge) who had her oracle there, and was guarded by a dragon (usually depicted as an enormous snake) known as Python. Apollo slew the monster with an arrow and left the corpse to rot thus giving the site its other name, Pytho, from the Greek pythein (“to rot”). This coin from Croton (right) shows Apollo shooting the Python with the sacred tripod between the two of them. Even though he was a god and the son of Zeus, he had still committed murder and had to be cleansed of the blood-guilt by working for eight years as a shepherd, minding the flocks of King Admetos of Pherai in Thessaly.

Having dispossessed the original owner, the god now pondered  the question of who was to look after and administer his cult. As he did so, he happened to spy a boatload of Cretans from Knossos sailing by on their way to Pylos. Taking the shape of a dolphin he swam out to meet them and leapt onto the boat. Needless to say, the Cretans were terrified and tried to flip him back into the water but to no avail. With the help of his father Zeus, he brought the ship right round the Peloponnese and up the Gulf of Corinth to Crisa, which lay on the coast below Delphi. There he revealed himself to them in all his divine splendour and spoke such soothing words to them that they immediately agreed to forsake their homeland and serve as his priests. Interestingly, the earliest small bronze votives (figurines and model tripods) date to about 800 BC and include a number of Cretan manufacture. The illustration (left) shows a bronze figure of a young man (kouros) in what is known as the Daedalic style, after Daedalus the master craftsman of Minos, the legendary king of Crete.

the question of who was to look after and administer his cult. As he did so, he happened to spy a boatload of Cretans from Knossos sailing by on their way to Pylos. Taking the shape of a dolphin he swam out to meet them and leapt onto the boat. Needless to say, the Cretans were terrified and tried to flip him back into the water but to no avail. With the help of his father Zeus, he brought the ship right round the Peloponnese and up the Gulf of Corinth to Crisa, which lay on the coast below Delphi. There he revealed himself to them in all his divine splendour and spoke such soothing words to them that they immediately agreed to forsake their homeland and serve as his priests. Interestingly, the earliest small bronze votives (figurines and model tripods) date to about 800 BC and include a number of Cretan manufacture. The illustration (left) shows a bronze figure of a young man (kouros) in what is known as the Daedalic style, after Daedalus the master craftsman of Minos, the legendary king of Crete.

Although dispossessed, Gaia was not a god to be treated lightly and she still maintained a presence at Delphi and continued to be worshipped alongside her successor. The fact that the sanctuary was one of a handful to have a woman in charge of the cult undoubtedly has a lot to do with the status of the earth-goddess. Also sharing the site was her daughter, Themis, and Poseidon, who was worshipped more because of his role as “Earth-shaker” (of huge importance in this seismically active region) than as god of the sea.

Dionysos

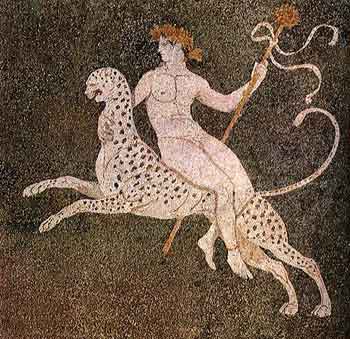

An interesting aspect of the cult at Delphi is that Apollo shared the site with his younger brother, Dionysos. Every year at the onset of winter, Apollo abandoned Delphi to spend three months  dwelling in the land of the Hyperboreans far to the north. It was a country of eternal youth and beauty, where old age and disease were completely unknown. In the meantime, the sanctuary on Parnassus was given over to the followers of the god of wine and revelry. The latter, known as maenades (“the raving ones”) who worked themselves into a frenzy through wine and dance. They roamed over the hillside in bands, dressed in fawn skins and wearing ivy wreaths on their heads (left). Each of them carried a thyrsus, a long stick wrapped in vine leaves.

dwelling in the land of the Hyperboreans far to the north. It was a country of eternal youth and beauty, where old age and disease were completely unknown. In the meantime, the sanctuary on Parnassus was given over to the followers of the god of wine and revelry. The latter, known as maenades (“the raving ones”) who worked themselves into a frenzy through wine and dance. They roamed over the hillside in bands, dressed in fawn skins and wearing ivy wreaths on their heads (left). Each of them carried a thyrsus, a long stick wrapped in vine leaves.

The descriptions of Dionysian rites are sensational, to say the least. Wild, orgiastic sex was definitely on the menu as were the wild animals that were hunted down, torn to pieces and eaten raw—in some stories, the same fate awaited any men they happened to come across. The contrast with the cult of the calm, rational Apollo could not be greater.

Ancient Sources

Many ancient writers have had something to say about Delphi. Most of them were historians and so their interest was centred around historical events, such as the Sacred Wars, or to specific prophecies that related to those events. Poets and playwrights have also left their accounts, which generally focus on the mythology. The most important sources are:

Plutarch: Plutarch was born in AD46 to a well-to-do family in the small town of Chaeronea in Boeotia, about 35 km. east of Delphi. He studied philosophy and mathematics at the Academy in Athens and was widely respected as an historian, biographer and essayist. For many years he served as the senior priest of Apollo at Delphi and was a close friend of Clea, the Pythia at the time. Among the works that bear most directly on Delphi are, On the ‘E’ at Delphi and On the Failure of Oracles.

Pausanias: One of the reasons that we know so much about the physical appearance of ancient Delphi is through the works of one of the first travel writers. Pausanias travelled through Greece in the 2nd century AD and recorded what he saw in the order that he saw it in his work, Periegesis Hellados (Description of Greece). So at Delphi he records the monuments as he climbed the Sacred Way up to the temple of Apollo. We do have some inscriptions, which corroborate his description but for the most part “without him the ruins of Greece would be a labyrinth without a clue, a riddle without an answer,” according to James Frazier, classicist and anthropologist.

Diodorus Siculus: Diodorus was born sometime in the 1st century BC in what is now Agira in Sicily. His great work was the Bibliotheca  Historica, a univeral history of the world compiled from the writings ofearlier historians. Not all of it survives but there are extensive tracts on the history and geography of Greece.

Historica, a univeral history of the world compiled from the writings ofearlier historians. Not all of it survives but there are extensive tracts on the history and geography of Greece.

Strabo (shown, left, in a 16th century engraving): was born in 64/63 BC to a wealthy and influential family from Pontus, a land on the southern shoreof the Black Sea in what is now Turkey. His principal work, the Geographica, was an immense 17 volume encyclopaedia of geographical knowledge that has suvived amost entirely intact.

Pliny the Elder: was born to a well-to-do Roman family in AD 23 and died while leading rescue efforts at Pompeii during the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. He had a long career as a soldier and administrator during the reigns of Claudius, Nero and Vespasian but also found time to turn his hand to writing history. His only surviving work, Naturalis Historia, was even larger than Strabo’s, running to 37 volumes.

The Pythia

The sanctuary of Pythian Apollo was by far the most famous oracle in the world in those days and was consulted by kings and commoners alike. According to the ancient accounts, his temple was situated over a crack in the earth from which intoxicating fumes (from the rotting corpse of Pytho, some say) issued forth. This caused the priestess who breathed them to go into a sort of trance from which she would communicate prophetic utterances.

According to Diodorus Siculus, writing in the first century AD, the special qualities of the site were first discovered by goatherds who noticed the effect the place had on their flocks:

They say that the manner of its discovery was the following. There is a chasm at this place where now is situated what is known as the “forbidden” sanctuary, and as goats had been wont to feed about this because Delphi had not as yet been settled, invariably any goat that approached the chasm and peered into it would leap about in an extraordinary fashion and utter a sound quite  different from what it was formerly wont to emit.

different from what it was formerly wont to emit.

The herdsman in charge of the goats marvelled at the strange phenomenon and having approached the chasm and peeped down it to discover what it was, had the same experience as the goats, for the goats began to act like beings possessed and the goatherd also began to foretell future events. After this as the report was bruited among the people of the vicinity concerning the experience of those who approached the chasm, an increasing number of persons visited the place and, as they all tested it because of its miraculous character, whosoever approached the spot became inspired. For these reasons the oracle came to be regarded as a marvel and to be considered the prophecy-giving shrine of Earth.

For some time all who wished to obtain a prophecy approached the chasm and made their prophetic replies to one another; but later, since many were leaping down into the chasm under the influence of their frenzy and all disappeared, it seemed best to the dwellers in that region, in order to eliminate the risk, to station one woman there as a single prophetess for all and to have the oracles told through her. And for her a contrivance was devised which she could safely mount, then become inspired and give prophecies to those who so desired.

And this contrivance has three supports and hence was called a tripod, and, I dare say, all the bronze tripods which are constructed even to this day are made in imitation of this contrivance. In what manner, then, the oracle was discovered and for what reasons the tripod was devised I think I have told at sufficient length.

Bibliotheca historia, XVI: 26 (2-5)

She was known as the Pythia and was originally chosen from among the young maidens of the vicinity. Because she served the god, she had to be without physical defect and a virgin. But this soon changed. According to Diodorus, a Thessalian named Echecrates was so smitten by the priestess that he kidnapped and raped her.

And, the Delphians because of this deplorable occurrence passed a law that in future a virgin should no longer prophesy but that an elderly woman of fifty should declare the oracles and that she should be dressed in the costume of a virgin, as a sort of reminder of the prophetess of olden times.

Bibliotheca historia, XVI: 26 (6)

Nowhere in the ancient literature is there a clear description of the selection process. Modern scholars have speculated that there may have been a sort of guild of women who looked after the sacred flame. Presumably they were of unblemished character and no longer had an active sex life—the gods (especially Apollo) were touchy about competition. The position commanded great respect—far more than was granted ordinary women. They were provided with a salary and housed at state expense. They were exempt from taxation, could own property and attend public events. At the height of its fame the sanctuary employed as many as three Pythiai, working in shifts, so great were the number of petitioners.

In addition to the Pythiai, there were a number of other temple personnel. There was a male priest (increased to two after 200 BC) who was chosen from among the leading citizens of Delphi and who looked after the day-to-day running of the sanctuary and was in charge of the Pythian Games, held in honour of the god. We know far less about the other officials associated with the cult, the hosioi (“holy ones”) and the prophētai. The latter are referred to in the ancient sources but their function is unclear. Prophētēs is the origin of the English word “prophet” but a better translation of the Greek would be something like “he who speaks on behalf of someone else” so they would seem to be involved in framing the petitioner’s questions. All that we know about the hosioi is that there were five of them.

Procedure

Consulting the oracle was not a ‘mystery’ in the technical sense as far as the ancient Greeks were concerned. In other words, discussion of the rituals involved was not forbidden. Nevertheless, it is a subject that we know relatively little about. The ancient sources seem to take the attitude that the procedure was so well known in their day that they did not need to go into great detail. The most important sources date from the early years of the Roman Empire and we have no idea how much their descriptions apply to earlier periods. According to Plutarch (Moralia, 292 D), in his day the Pythia normally made pronouncements once a month, apart from the three winter months, on the seventh day.

Ion, the hero of Euripides play of the same name, was a junior priest at Delphi, and responsible for getting the temple precinct ready for the day’s events. In the course of the play he describes his routine:

But I will labour at the task that has been mine from childhood, with laurel boughs and sacred wreaths making pure the entrance to Phoebus’ temple, and the ground moist with drops of water; and with my bow I will chase the crowds of birds that harm the holy offerings.

Euripides, Ion, lines 100-110

There would undoubtedly have been a period of fasting in the days leading up to the main event. Then the Oracle would bathe in the Castalia Spring and undergo a ritual purification involving barley smoke. Before entering the temple she drank from the sacred  waters of the Kassotis spring which, according to Pausanias, flowed into a cistern just above the temple. Its waters were supposed to inspire prophecies. From there, the Pythia made her way to the adyton (which means something like “off limits”), the holiest part of the temple. She sat on a tripod placed close to the omphalos and the cleft in the rock. Holding a laurel branch in one hand and a dish of Kassotis water in the other, she inhaled the sacred fumes (pneuma).

waters of the Kassotis spring which, according to Pausanias, flowed into a cistern just above the temple. Its waters were supposed to inspire prophecies. From there, the Pythia made her way to the adyton (which means something like “off limits”), the holiest part of the temple. She sat on a tripod placed close to the omphalos and the cleft in the rock. Holding a laurel branch in one hand and a dish of Kassotis water in the other, she inhaled the sacred fumes (pneuma).

The petitioners, too, undertook a series of rituals, including purification in the Castalia Spring. They then took part in a solemn procession up the Sacred Way to the temple. There they drew drew lots to determine the order in which they presented their questions. Highly esteemed individuals or cities (because of their rich donations in the past) were able to jump the queue. Each of them had to pay a fee to the temple and sacrifice an animal, in most cases a goat (in honour of the site’s discoverer). Plutarch describes the scene:

And what is the significance of the libations poured over the victims and the refusal to give responses unless the whole victim from the hoof-joints up is seized with a trembling and quivering, as the libation is poured over it? Shaking the head is not enough, as in other sacrifices, but the tossing and quivering must extend to all parts of the animal alike accompanied by a tremulous sound; and unless this takes place they say that the oracle is not functioning, and do not even bring in the prophetic priestess.

Plutarch, Moralia 385

After it was slaughtered, it was opened up and its organs inspected to ensure that there were no defects. Once, according to Plutarch, when a petitioner insisted on proceeding despite the bad omens, the priestess went into a violent frenzy and died soon afterwards. If the sacrifice was deemed auspicious, the petitioner was then led into the temple where he waited just outside the adyton to pose his question. He goes on to say:

It is a fact that the room in which they seat those who would consult the god is filled, not frequently or with any regularity, but as it may chance from time to time, with a delightful fragrance coming on a current of air which bears it towards the worshippers, as if its source were in the holy of holies; and it is like the odour which the most exquisite and costly perfumes send forth.

Plutarch, Moralia 387

He was allowed only one question and this was normally put to the priestess through one of her attendant priests. Intoxicated by the fumes, the Pythia gazed into her dish of holy water, shaking her laurel branch as the spirit of the god passed through her. She then gave her reply, which was written down by a priest and given to the questioner. Strabo tells us that, ...the Pythian priestess receives the breath and then utters oracles in both verse and prose, though the latter too are put into verse by poets who are in the service of the temple. Strabo, Geography IX, 3 |

|

Many modern scholars take the view that the actual utterances were mainly unintelligible gibberish and that it was the priests who interpreted her responses and cast them into verse. Since the site received visitors from all over the world, it was argued, they were in a position to gather intelligence and make informed decisions. However, the ancient writers are  unanimous in insisting that it was the oracle herself who made the pronouncements. Many of the questions asked of the Pythia have survived inscribed on lead tablets but none of the answers were recorded by the priests.

unanimous in insisting that it was the oracle herself who made the pronouncements. Many of the questions asked of the Pythia have survived inscribed on lead tablets but none of the answers were recorded by the priests.

The most famous answer that we know was recorded again by Herodotus when Croesus (left, on his funeral pyre), the fabulously wealthy king of Lydia, asked the Pythia whether he should cross the Halys River and attack the Persian king, Cyrus the Great. The Pythia's typically enigmatic reply was if Croesus should cross the Halys River, a great empire would fall. Heartened by this answer he did attack Persia but it was he, Croesus, who was defeated. The one boon that Croesus requested of Cyrus upon his capture was to have his manacles sent to Delphi as a rebuke to the oracle that had failed him after he had bestowed so many luxurious gifts on the sanctuary. Unabashed, the Pythia retorted that Croesus had failed to follow up on the first response and ask which empire she meant.

The Pythian Games

Delphi was also the site of the Pythian games, which were instituted by the god in self-imposed penance for the slaying of Python and were only second in importance to those at Olympia. Originally held every eight years it had become a  quadrennial event by 582 BC.

quadrennial event by 582 BC.

Because Apollo was the god of music and the arts, the games here had a very different flavour. The first event was for singing a hymn to the god, but soon the usual athletic contests such as running, riding and chariot racing, joined other contests for singing, dancing, flute and lyre playing. Homer is said to have visited the site but did not compete. The poet Hesiod was reputedly disqualified for not knowing how to play a harp while he sang. These events were held in the theatre above the temple and the stadium nestled in the pine forest above the sanctuary. The prize at the games was a laurel wreath gathered at the Vale of Tempe. The bay-laurel was sacred to Apollo and commemorated the “one that got away.” Fleeing the god, who had serious designs on her maidenhood, the nymph Daphne was turned into a laurel tree by her protective father, the river-god Penaeus.