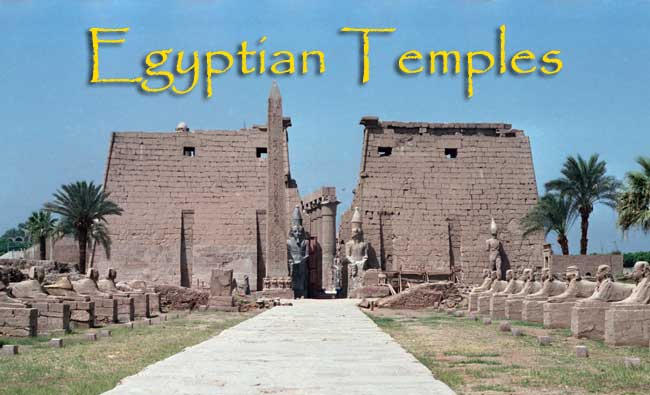

This is intended to be the first in a series of articles dealing with Egyptian Temples, and to serve as a general introduction to the subject. It describes the standard sort of temple complex which emerged in the New Kingdom Period (1550-1069 BC) and continued in fashion down to Roman times.

During the New Kingdom Period in Egypt, roughly the latter half of the second millennium BC, there were two principal types of temple— cult temples, known as “mansions of the gods” and mortuary temples, known as “mansions of millions of years”. Cult temples were dedicated to the worship of the gods of Egypt— Amun, Ptah, Horus, Osiris, etc.— and were designed to  accommodate their images. In mortuary temples, on the other hand, the object of worship was the deified pharaoh. We are fortunate that sufficient examples of both types have survived in reasonably good condition so that the layout and much of the superstructure are available for study. However, a lot of the details of decoration and furnishing have disappeared and we have to rely on written descriptions and contemporary depictions in order to reconstruct these. These also help considerably in enabling us to understand the functions of the various rooms and buildings.

accommodate their images. In mortuary temples, on the other hand, the object of worship was the deified pharaoh. We are fortunate that sufficient examples of both types have survived in reasonably good condition so that the layout and much of the superstructure are available for study. However, a lot of the details of decoration and furnishing have disappeared and we have to rely on written descriptions and contemporary depictions in order to reconstruct these. These also help considerably in enabling us to understand the functions of the various rooms and buildings.

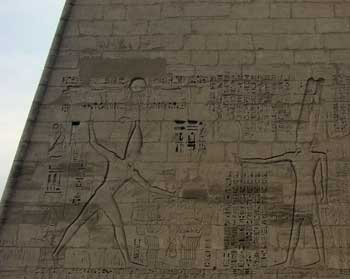

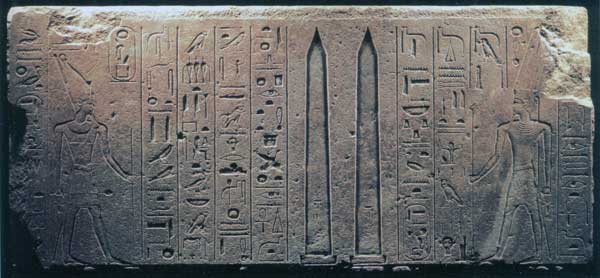

Building texts are fairly abundant from the New Kingdom down to Roman times and describe the construction, circumstances and function of several temples. The various components are named, described and their purpose outlined— there are even detailed descriptions of the fittings (doors, etc.). Great officials, in their Tomb Biographies, describe the roles they played, as chief of works or treasurer, in these projects. Senenmut (left), for example, gives a detailed description of the quarrying, transport and installation of Hatshepsut's obelisks at Karnak. This type of document tends to be stereotypical, however, and should be applied cautiously on a case by case basis.

Relief from the Red Chapel showing Hatshepsut's Obelisks

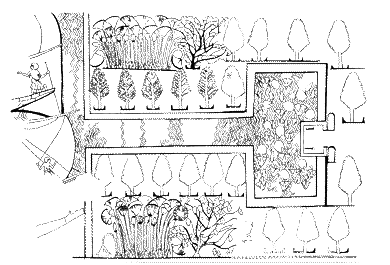

Representations of temples occur frequently on tomb walls, especially at Amarna, and in papyri. Pylons, the great formal gates to the temples, are most frequently depicted but other details which do not survive appear as well. The ground plan of a temple at Heliopolis, possibly that of Re'-Harakhty himself, appears on a stone slab and shows three open courtyards and a number of subsidiary temples.

Modern Farmstead near Abydos

The forms of Egyptian architecture are based on the reed huts of the first people to settle beside the Nile. Bundles of reeds or reed poles framed and supported rush mats to make their simple huts and small shrines—techniques that are still in use today. These were simply translated to stone for the permanent use of the gods. Of course, the temples of later periods are much grander in scale and elaborate but otherwise nothing really new is added to the mix.

Mansions of the Gods

The big occasion of the Egyptian year was the festival of the local deity and the layout of the temple was largely determined by the requirements of ritual and ceremony. Essentially, the whole temple complex was meant to be a recreation of the Primeval Mound where life began. At the heart of these ceremonies was a great procession when the god emerged from his temple, just as life emerged from the cosmic ooze on the original mound. However, it was the home of the deity too and, in that respect, functioned in pretty much the same way as any noble household—it was only a matter of degree. The god had to be fed, and so there were kitchens and dining rooms. There were also robing rooms along with plenty of closet space and vaults full of jewellery.

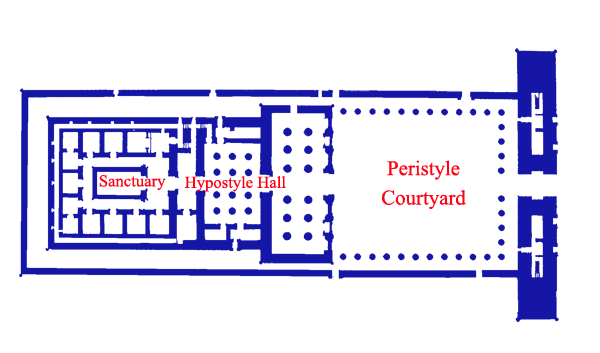

Ground Plan of the Temple of Horus. Edfu

The standard temple followed a tripartite plan, consisting of an outer court, a hypostyle (or columned) hall, and the sanctuary itself. These elements could be multiplied and were generally enclosed by auxiliary rooms but the basic design was fairly consistent. A common addition was an enormous gateway known as a pylon at the entrance to the courtyard, providing a more grandiose approach. The various elements were arranged symmetrically, along a single avenue of approach, ideally running from east to west and facing the Nile (although this combination was not always possible). It was meant to be a microcosm of the cosmos at the time of Creation.

View of the Luxor Temple from the Nile

The ancient Egyptians believed that the world began with the emergence of the Primeval Mound from the watery abyss. The obvious inspiration was the reappearance of the land after the annual inundation and the way that life seemed to burst forth spontaneously from the fresh silt laid down by the river. The sanctuary represented the mound of creation and was higher than the rest of the temple. The columns of the Hypostyle Hall were carved in the shape of lotuses, lilies and papyrus plants, a reproduction of the marshes surrounding it. In the myth, the creator god lived in a simple reed hut on the mound and, although translated to stone, the sanctuary always retained that original form. Each year the god left the sanctuary, to travel through the streets of the city and visit the other gods. In this procession, he was carried in sacred boat on the shoulders of his priests, gliding through the sacred swamp to receive the adoration of his worshippers. Typically, there was a rise in floor level towards the sanctuary from the outside while the ceiling got progressively lower. Approaching the god, you would move from the bright sun beating down on the open courtyard, through a rather dimly lit hall to the complete darkness of the dark, claustrophobic sanctuary, heightening the sense of mystery and awe. As we shall see in future articles, there was plenty of room for variety within this basic concept.

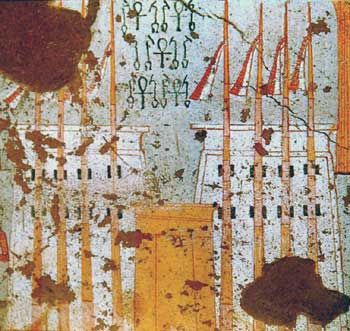

Boat Procession. Red Chapel at Karnak

Given its geography, transportation in Egypt was primarily by water and most temples had their own stone quay at the riverside or at the end of a canal or basin that was linked to the river. Only the foundations of the quay at Karnak have been uncovered but it is depicted on the walls of one of the Theban tombs—a rectangular basin with a tree-lined canal and a stone pier.

Avenue of Sphinxes at Karnak

The processional way was often lined with monuments and statues of various types—most often sphinxes— which marked its route and offered their protection to the god. At some temples the sphinxes had animal heads, usually  associated with the god or goddess worshipped there— the ones at Karnak were ram-headed, for example— while at others the face was that of the pharaoh. Barque Shrines, such as the ones shown (left) from Karnak, were placed at regular intervals along the route, to provide a shady spot for god and the priests who were carrying him to rest and restore themselves before continuing their journey.

associated with the god or goddess worshipped there— the ones at Karnak were ram-headed, for example— while at others the face was that of the pharaoh. Barque Shrines, such as the ones shown (left) from Karnak, were placed at regular intervals along the route, to provide a shady spot for god and the priests who were carrying him to rest and restore themselves before continuing their journey.

The temple proper was surrounded by huge mud-brick walls, up to 10 metres thick which, in addition to isolating the sacred realm of the god from the everyday humdrum of the material world, served to protect it from the ravages of flood and human conflict. The walls also served a symbolic purpose and the courses of brickwork were laid in wavy lines, imitating the waters of the abyss.

The Enclosure Wall at Karnak

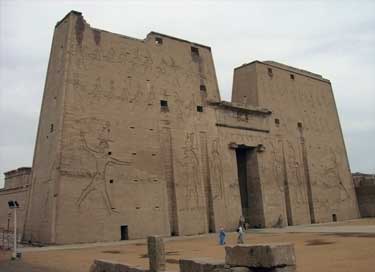

The Pylon

The Pylon (bekhen) consisted of a pair of large, rectangular towers with slightly sloping faces flanking a central, much lower gateway. They have what are known as torus mouldings along the edges, recreating in stone the bundles used to strengthen the corners of the reed originals—the fence and gateway that surrounded the earliest simple huts. The vegetal motif also appears in the cavetto cornice at the top of the walls, the curve of which replicates the drooping heads of the plants that had been woven together as mats.

The Pylon (bekhen) consisted of a pair of large, rectangular towers with slightly sloping faces flanking a central, much lower gateway. They have what are known as torus mouldings along the edges, recreating in stone the bundles used to strengthen the corners of the reed originals—the fence and gateway that surrounded the earliest simple huts. The vegetal motif also appears in the cavetto cornice at the top of the walls, the curve of which replicates the drooping heads of the plants that had been woven together as mats.

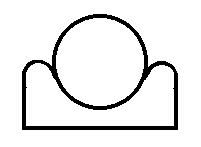

The two halves of the pylon flanked a central, somewhat lower, gateway from which the god would emerge through a set of double-doors on festival days. To the Egyptians, the form signified the rising sun and could be read as the hieroglyph for ‘horizon.’ It was the “Luminous Mountain Horizon of Heaven” and a depiction of the winged sun disc was often carved above the doorway, or emblazoned in gold leaf on the door itself. Stairways inside the body of the pylon led to the top of the gateway where the pharaoh would present himself on grand state occasions, appearing like the rising sun to his subjects below.

Tumbled Stonework from the Outer Pylon of the Ramesseum

The towers were built entirely of stone with an outer casing of large blocks and a core of loose stone, often recycled from earlier monuments that might have been in the way or belonged to pharaohs who were later discredited, such as Hatshepsut or the great heretic Akhenaten.  The stones were hauled to the top by means of mud brick ramps. When the structured was complete, the surface decoration was applied from top to bottom as the ramp was gradually dismantled. Because it was never finished (and because the courtyard behind it was filled with sand until the nineteenth century), the construction ramp on the inside of Pylon I at Karnak still survives.

The stones were hauled to the top by means of mud brick ramps. When the structured was complete, the surface decoration was applied from top to bottom as the ramp was gradually dismantled. Because it was never finished (and because the courtyard behind it was filled with sand until the nineteenth century), the construction ramp on the inside of Pylon I at Karnak still survives.

To the vast majority of Egyptians, the outside of the pylon was as much as they would ever see of the temple. Because of its size and prominence, it was the ideal setting for display and propaganda—usually centring around the pharaoh who built the temple rather than on the god or goddess who resided there. The exterior face was normally carved with sunken reliefs depicting the pharaoh as the great warrior, the protector of Egypt and smiter of her enemies. The reliefs and statues were brightly painted and would have presented a colourful contrast to the stark mud-brick to be seen today. It was a common practice for later pharaohs to re-carve the inscriptions and claim the deeds as their own. Many pharaohs erected obelisks in front of their pylons and Ramesses II in particular was fond of placing colossal statues of himself there. The effect was further enhanced by pennants fluttering from tall wooden flagstaffs placed in tall niches— the stone sockets can be seen today. These flagstaffs were not merely decorative, however. The staff with its fluttering pennant was the hieroglyphic symbol for ‘god.’

Successive pylons at Philae

The more elaborate temples had a series of pylons, separating a number of courtyards and halls. At Karnak, there was a second series leading away, perpendicular to the main axis, to the Luxor Temple which lay about two kilometres away to the north.

Obelisks

Obelisks (tekhen) were a very ancient and characteristically Egyptian type of dedication. Originally they were probably amorphous stones, set upright to represent the benben on which the rays of the rising sun first fell at the dawn of creation. The original was at the temple of the sun-god at Heliopolis and was believed to represent the petrified semen of Re’-Atum. The New Kingdom versions were most often erected in pairs, flanking the entrance to the temple or separating one element of the complex from the next. They were long, tapering four-sided shafts with a pointed pyramidion at the top. The sides were carved with reliefs and inscriptions commemorating significant events in the reign of the pharaoh. Hewn out of a single block of stone, they could reach as high as 30 metres or more and might weigh as much as several dozen tons. Their quarrying, transport and erection was an enormous undertaking and pharaohs did not hesitate to advertise the fact.

Obelisks (tekhen) were a very ancient and characteristically Egyptian type of dedication. Originally they were probably amorphous stones, set upright to represent the benben on which the rays of the rising sun first fell at the dawn of creation. The original was at the temple of the sun-god at Heliopolis and was believed to represent the petrified semen of Re’-Atum. The New Kingdom versions were most often erected in pairs, flanking the entrance to the temple or separating one element of the complex from the next. They were long, tapering four-sided shafts with a pointed pyramidion at the top. The sides were carved with reliefs and inscriptions commemorating significant events in the reign of the pharaoh. Hewn out of a single block of stone, they could reach as high as 30 metres or more and might weigh as much as several dozen tons. Their quarrying, transport and erection was an enormous undertaking and pharaohs did not hesitate to advertise the fact.

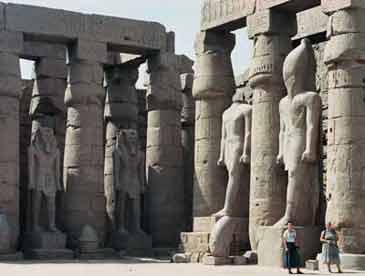

The Outer Courts

The Forecourt (wba) which lay behind the pylon was a large space, used for the assembly of fairly large numbers of people, and formed a link between the realms of gods and men. It was normally what is known as a peristyle courtyard which means that there was a colonnade running along its perimeter. The space was kept as uncluttered as possible and whatever structures existed were generally tucked off to one side.

The Forecourt at the Temple of Horus, Edfu

First and foremost, it was where the appropriate purification rituals were undertaken by the pharaoh and priests before they could enter the temple proper. Usually there were altars off to the side of the principal axis where burnt offerings of sacrificial animals were made to whichever god or gods were worshipped within. Booty and tribute from the subject lands and gifts from  Egypt’s allies would be laid before the god. When the god travelled, this was this was the place from which he departed and to which he returned, and there was often one or more bark shrines for his rest and repose. The setting was considered ideal for the display of statues—those of kings and commoners alike. A large number of statues have been recovered from large pits (known today as ‘cachettes’) in the courtyards of the Karnak and Luxor Temple—the latest at Luxor in 1989.

Egypt’s allies would be laid before the god. When the god travelled, this was this was the place from which he departed and to which he returned, and there was often one or more bark shrines for his rest and repose. The setting was considered ideal for the display of statues—those of kings and commoners alike. A large number of statues have been recovered from large pits (known today as ‘cachettes’) in the courtyards of the Karnak and Luxor Temple—the latest at Luxor in 1989.

The royal statues were most often set in the spaces between the columns lining the perimeter and acted as protectors of the sacred space. They often took the appearance of the god Osiris, wrapped up like a mummy with only the head showing. There are also a number, such as that of Tuthmosis III (left) showing the pharaoh presenting offerings of jars of oil to the deity. The private statues were mainly votives, placed in the courtyard to thank the gods for their blessings (real or anticipated) and to remind the gods, by their perpetual presence, of their piety. They generally showed the individual squatting on the ground (the so-called ‘block’ statues, see the statue of Senenmut, above). The outer courtyard was open and accessible to high-ranking officials and selected representatives of the general public. The reliefs on the walls depict the pharaoh’s prowess in battle or his relations with the gods. The rest of the temple, the roofed area, was restricted to all but the pharaoh and the priests.

The Hypostyle Hall

Ramesseum. The Hypostyle Hall

The Hypostyle Hall (wadjit) sits across the main axis of the temple and is normally as broad as the width of the courtyard in front of it. Sometimes it was separated from the courtyard by another  pylon, as was the case with the great hypostyle hall of Seti I at Karnak, but in other cases, such as at Luxor, the hall was added directly to the courtyard with only a balustrade to separate them.

pylon, as was the case with the great hypostyle hall of Seti I at Karnak, but in other cases, such as at Luxor, the hall was added directly to the courtyard with only a balustrade to separate them.

The main entrance was through a door on the main axis, used for the ‘boat-procession’ of the god—side doors were used for the regular offerings of food and drink. Apart from the centre aisle, the interior was entirely filled with columns to the extent that the distance between them was less than the thickness of each. This was because, in the Old Kingdom period, the stone lintels that supported the ceiling were liable to crack under the strain if they were much more than three metres long. Even when better quality stone became available in later periods, such was the conservatism of Egyptian builders that they stuck to the original ratio.

The Hypostyle Hall had two important symbolic meanings. In the Egyptian cosmology, the heavens were supported by columns and the columns of the hall are often seen in that light, but in other instances they represent the marshes that surround the Mound of Creation, symbolized by the inner sanctuary of the temple, where life began. For that reason, plant forms typical of that environment, especially the papyrus, were used for the columns.

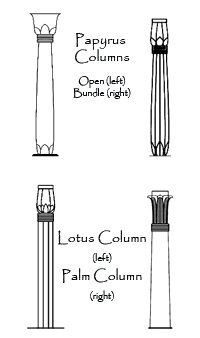

Columns

Egyptian columns came in a variety of types—over 30 have been identified—with the selection depending on the setting in which they were used. The original reed structures were supported by a framework of trunks or bundles of papyrus reeds and so stone versions were used (for the most part) in the temples. The two top examples in the diagram (right) are based on the papyrus plant—in both single-stemmed and bundled versions. Even the ties lashing the stems together are reproduced. In most cases, the open forms are preferred along the main axis of the complex while buds are found in the more peripheral areas such as the outer courts.

Other columns were based on the palm and the lotus. The former actually consisted of eight palm fronds tied to a pole while the latter have ribbed shafts, representing the plant’s stem and also come in both open and closed versions. In addition, there were a few specialized types such as the ‘tent-pole’ columns used in the Festival Hall of Tuthmosis III at Karnak or the ‘Hathor columns’ bearing the face of the cow-headed goddess found at Hatshepsut’s Temple at Deir el-Bahri among other places.

The Sanctuary

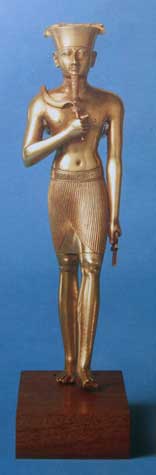

The most sacred and intimate part of the temple was the tiny room at the back of the building where the image of the god was kept. It was accessible only to the king and the high priests. The design of most of them was based on that of the original reed hut which housed the totems of their prehistoric ancestors. The sanctuary was on the main axis of the temple with a set of double doors looking back towards the entrance. If there was more than one deity involved—in a triad for example—the shrines of the secondary ones would be off to the side. The other principal type was the barque shrine, a narrow, open-ended structure with a plinth in the centre to hold the sacred boat containing the statue of the god. The one at Karnak, dedicated by the Macedonian king, Philip Arrhidaeus, is shown here (left). The walls were decorated with reliefs depicting the most intimate details of cult practice.

The most sacred and intimate part of the temple was the tiny room at the back of the building where the image of the god was kept. It was accessible only to the king and the high priests. The design of most of them was based on that of the original reed hut which housed the totems of their prehistoric ancestors. The sanctuary was on the main axis of the temple with a set of double doors looking back towards the entrance. If there was more than one deity involved—in a triad for example—the shrines of the secondary ones would be off to the side. The other principal type was the barque shrine, a narrow, open-ended structure with a plinth in the centre to hold the sacred boat containing the statue of the god. The one at Karnak, dedicated by the Macedonian king, Philip Arrhidaeus, is shown here (left). The walls were decorated with reliefs depicting the most intimate details of cult practice.

The cult image itself might be of gilded wood or stone but was often were of solid gold or silver (representing the divine flesh of the gods). The eye-sockets were generally inset with semi-precious stones and inlays of lapis lazuli were used to represent the hair. Under the circumstances, it is hardly surprising that none of these statues have survived.

Other Features

Arranged around the core of the temple were a number of subsidiary rooms including smaller shrines for the use of visiting deities, storerooms for the god's fine robes and jewellery, and robing rooms for the priests. In many temples the room before the sanctuary was used as an Offering Hall, the place where the daily sacrifices to the god were made. All temples included a Barque Shrine where the sacred boat used to transport the deity was kept. Since virtually all transportation in the Nile Valley was by boat, it was logical to assume that that was how the gods travelled as well. However, the god did not use a real boat but a smaller, portable version which could be carried on the shoulders of his priests. Normally the shrine was located just before the Sanctuary proper but in many instances the Sanctuary itself was a barque shrine making a second one unnecessary. Above left is a replica of the sacred barque from the Horus Temple at Edfu.

Arranged around the core of the temple were a number of subsidiary rooms including smaller shrines for the use of visiting deities, storerooms for the god's fine robes and jewellery, and robing rooms for the priests. In many temples the room before the sanctuary was used as an Offering Hall, the place where the daily sacrifices to the god were made. All temples included a Barque Shrine where the sacred boat used to transport the deity was kept. Since virtually all transportation in the Nile Valley was by boat, it was logical to assume that that was how the gods travelled as well. However, the god did not use a real boat but a smaller, portable version which could be carried on the shoulders of his priests. Normally the shrine was located just before the Sanctuary proper but in many instances the Sanctuary itself was a barque shrine making a second one unnecessary. Above left is a replica of the sacred barque from the Horus Temple at Edfu.

The temple also included a number of kitchens and workshops to provide for the everyday requirements of the cult. The god needed to be fed, which meant bakers, butchers and brewers. Jewellery and clothing were manufactured and repaired on the spot. In fact, just about anything used in the temple was made in its own workshops. In addition, a huge amount of space was given over to storage magazines and granaries.

The Sacred Lake at Dendera

Most temples had a Sacred Lake (shi-netjer) within the precinct, used for lustral purposes and to provide fresh water for the temple. They were generally rectangular, lined with stone, and had steps leading down to the water.